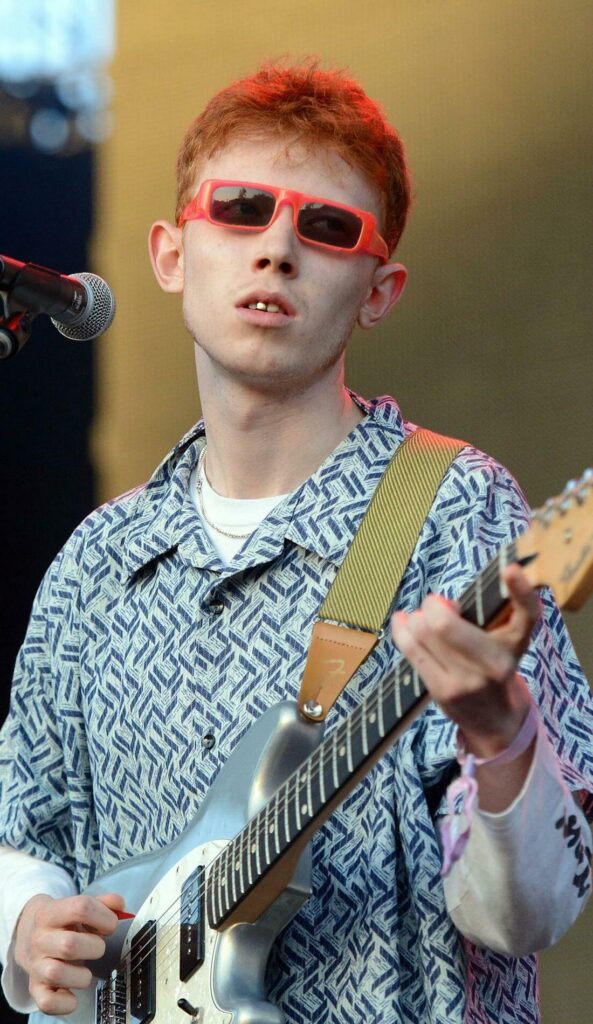

It’s unlikely you’ll read an interview with Archy Marshall, aka King Krule, without, at some point, hearing about his hair. This makes sense when you see it up close; it’s extremely red. “A lot of people think I’m Irish,” he tells me, hunched over a pint of Coca-Cola. “I wonder why they think that? I don’t sound Irish on the records . . . ”

We’re in a pub in Rotherhithe, south London, next to the Thames. Across the river is Wapping and, beyond that, the afternoon sun glances off the Shard and the sloped side of the Leadenhall Building. Marshall, 28, grew up not far from here. South London — south-east London in particular — has framed most of his life and work. Ten years ago, not long after his time studying at Croydon’s Brit School for performing arts, it provided the backdrop for his debut album, 6 Feet Beneath the Moon, basing his moniker on the 1958 Elvis Presley movie King Creole.

The album was an instant hit. Elevated by critics, it catapulted Marshall to prominence at the age of 19. When the LP reached the US, he was invited to play on Conan and the Late Show with David Letterman. Listeners on both sides of the Atlantic were struck by the fresh-faced teen with the crooning, rugged baritone — even Beyoncé, who endorsed his single ‘‘Easy Easy” to her millions of fans.

Since then, Marshall has released three more studio albums, including The Ooz (2017), which was nominated for the Mercury Prize, and Man Alive! (2020), split between punk anger and woozy pining — most likely due to his discovery, midway through recording, that he was going to be a father.

The internet helped make Marshall’s career. His first single, “Out Getting Ribs”, released in 2010 under the name Zoo Kid, was initially uploaded to Bandcamp, where it was picked up and circulated. However, Marshall doesn’t think a teenager today could repeat this rise to fame. “I feel sorry for all the up-and-coming TikTok people . . . they’re constantly promoting their shit. I never promoted my shit. I actually hated promoting it. I just play.”

On June 9, King Krule releases his new album Space Heavy. It has taken a couple of years to write, with some songs lifted and adapted from earlier projects. For Marshall, Space Heavy signifies his deliverance from something he calls “the gloop” — a form of writer’s block that came from creating surplus. “There was years, like with The Ooz or 6 Feet, where I’d turn round and it’d been two hours and I’d just looped one synthesiser over and over then basically just used 10 seconds of it,” he says. “[Space Heavy] was more rigid . . . every time I pressed record I wanted there to be an intention.”

Part of what makes King Krule stand out is Marshall’s magpie approach to songwriting. There are elements of post-punk as well as rockabilly, hip-hop, hardcore and jazz — Marshall grew up listening to Bill Evans, Oscar Peterson and Pharoah Sanders. He also has a special affection for samba and bossa nova.

While writing Space Heavy, Marshall spent a long time listening to Transa, the 1972 album by the exiled Brazilian composer Caetano Veloso. “He sings in English for a lot of it,” Marshall says, “and it’s very playful and naive. You can just tell there’s an ultimate freedom behind what he’s doing . . . there’s a release from the situation he was in . . . to then be in London and find a new home.”

Like Veloso, Marshall has also relocated recently, moving in 2019 to St Helen’s, a town near Wigan in north-west England, so that he could be closer to his four-year-old daughter. Two years later he settled in Everton, Liverpool, before moving back to London.

The lyrics for Space Heavy were largely composed during his train rides between the capital and the north-west. Liminality is a motif in the album, coming through in songs such as “Seaforth”, “Wednesday Overcast” and “If Only It Was Warmth”. It also inspired the album title: the heavy space between places.

“One of the things it was about was suspended animation,” Marshall says. “You’re out of the control of your responsibilities . . . One night it was midnight and I was going back to London, and the train stopped and there was a power cut for about two hours. I had no control over that and I quite liked it. I was in pitch black for two hours, no pressure whatsoever.”

King Krule’s records have always been thick with space. They echo like a lo-fi adaptation of a Phil Spector single, carried by Marshall’s reverb-heavy vocals. Like many songwriters, Marshall takes his call from the physical environment around him; lately, however, he’s been more drawn to the eerie industrial landscapes of the north than London. “I love the Victorian turn of the century . . . because it’s frightening and it’s explosive and it’s what set the tone for a lot of the change over the next hundred years. In the north-west, you’ve got all this history of industry and it’s just been a bit forgotten.”